About the Exhibitions and Highlights

Chapter One | The Changing Form of Chinese Characters

Chapter Two | Calligraphy of the Tang Dynasty: Until the Anshi Rebellion

Chapter Three | Calligraphy of the Tang Dynasty: Yan Zhenqing

Chapter Four | The Reception of Tang-dynasty Calligraphy in Japan

Chapter Five | The Appreciation of Yan Zhenqing in the Song Dynasty

Chapter Six | The Influence on Later Generations

Yan Zhenqing

(709–785; died age 77)

Yan Zhenqing hailed from Linyi in Langye (modern-day Shandong Province). His courtesy name was Qingchen. He passed the examination to become a civil servant at age 26. His upright, honest character vexed his superiors and he was demoted several times, but he came to the rescue of the imperiled Tang dynasty during the Anshi Rebellion. While inheriting earlier calligraphic traditions, his powerful writing style also broke new grounds.

Chapter One | The Changing Form of Chinese Characters

― The Secret Evolution of Calligraphic Script ―

As with letters, Chinese characters are used to write down words, preserve their meaning, and communicate them to other people. To fulfil these tasks, there needs to be a certain quantity of these characters and their usage needs to be systematized. The oldest extant examples of characters that match these stipulations are found on oracle bones dating back to China's Yin dynasty. The next examples date from the end of the Yin dynasty. Known as jinwen, these were inscribed on bronze vessels.

The characters were later standardized after the first Qin emperor unified the country in 221 B.C. This marked the establishment of seal script as the official script. Seal script has a sublime beauty marked by a right-to-left symmetry and an abundance of curved lines. However, it takes a long time to write out, so it was eventually simplified. This process led to the emergence of clerical script, which became the official script during the Later Han dynasty. Clerical script is characterized by strokes that sweep from the upper left to the lower right like heaving waves. The pursuit of practicality and faster writing then saw clerical script evolving into cursive and running script.

Eventually, clerical script was replaced by square-shaped standard script as the final official script. After the north and south of China were unified during the Sui dynasty, standard script reached its completed form around the start of the Tang dynasty. Marked by a beautiful symmetry, standard script remains the regular way of writing Chinese characters to this day.

Chapter Two | Calligraphy of the Tang Dynasty: Until the Anshi Rebellion

― The Inheritance of Wang Xizhi’s Traditions and the Completion of Standard Script ―

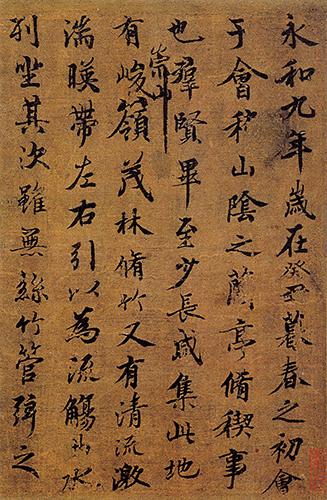

Wang Xizhi's penmanship was greatly admired by the second Tang emperor Taizong, who assumed the throne in 626. The emperor spent considerable sums collecting Xizhi's work from all over China. As a result, the opportunity to view Xizhi's calligraphy was lost to the general public. Taizong obtained Preface to the Lanting Pavilion, Xizhi's masterpiece, from the monk Biancai using underhand means. He then ordered Yu Shinan, Ouyang Xun, Chu Suiliang, and other master calligraphers to copy the original work, and he had his best artisans make elaborate reproductions. However, Taizong loved the work so much that he was buried with it, so the original was lost to the world after just 296 years in existence. In this way, Wang Xizhi was deified by Emperor Taizong.

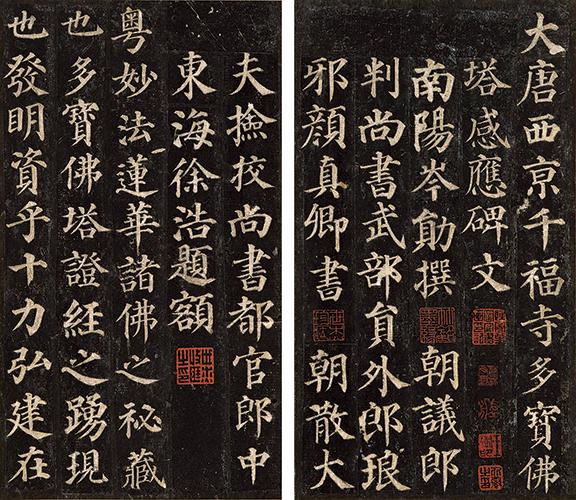

Ouyang Xun and Yu Shinan were born in the state of Chen and reached maturity during the Sui dynasty. In their later years, they both served under Emperor Taizong. While following in the traditions of Wang Xizhi, the two men perfected the use of standard script. Ouyang Xun produced the highly-accomplished Inscription on Stele at Sweet Spring, Jiucheng Palace, while Yu Shinan's masterpieces include Inscription on Confucius Mausoleum Stele, a gentle work with a concealed vigor. Chu Suiliang appeared on the scene around 40 years later. He produced Inscriptions on Yanta Pagoda Steles, which were infused by the opulent spirit of the Tang dynasty and whose writing style went on to dominate the world of calligraphy.

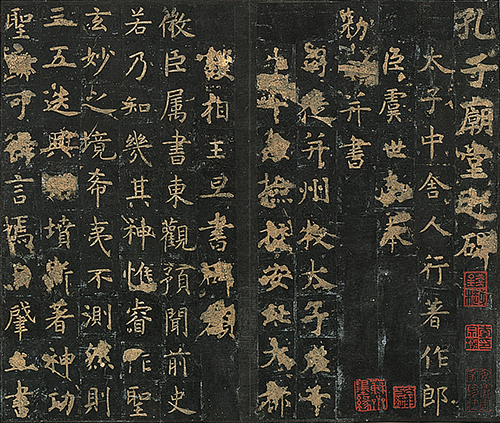

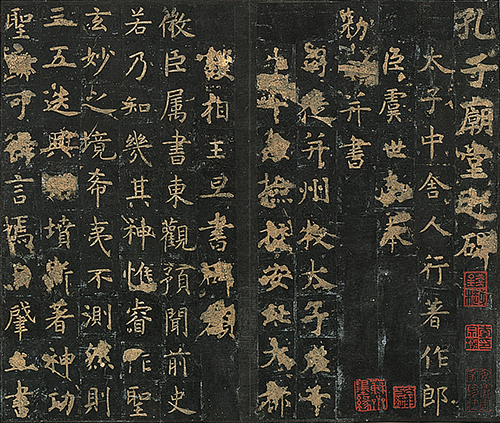

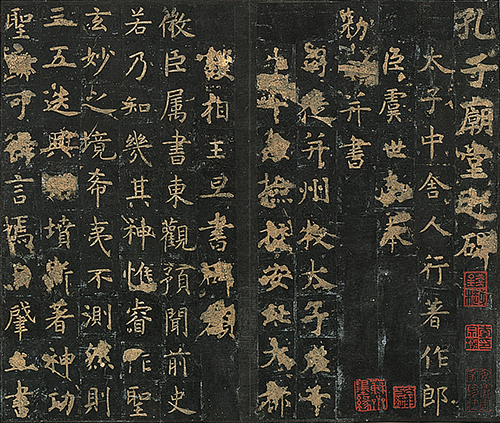

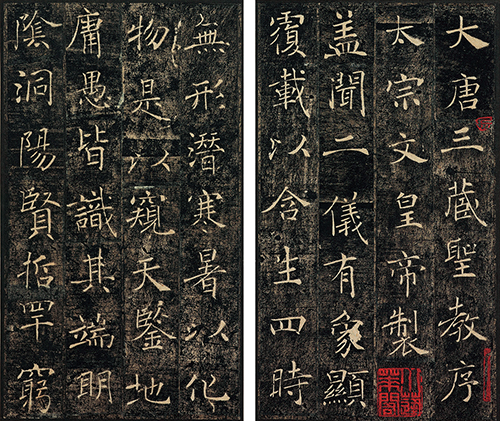

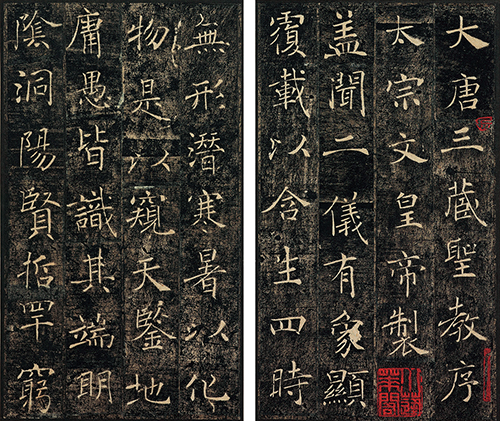

Inscription on Confucius Mausoleum Stele, Only Extant Tang Dynasty Rubbing

By Yu Shinan

Tang dynasty, dated 628–630

Mitsui Memorial Museum, Tokyo

By Yu Shinan

Tang dynasty, dated 628–630

Mitsui Memorial Museum, Tokyo

|

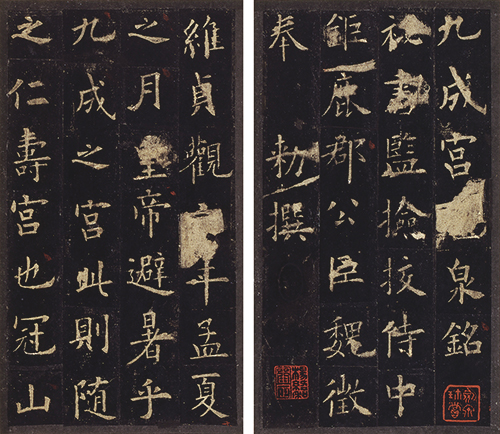

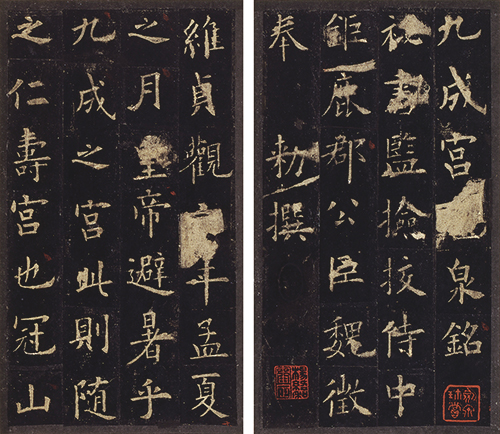

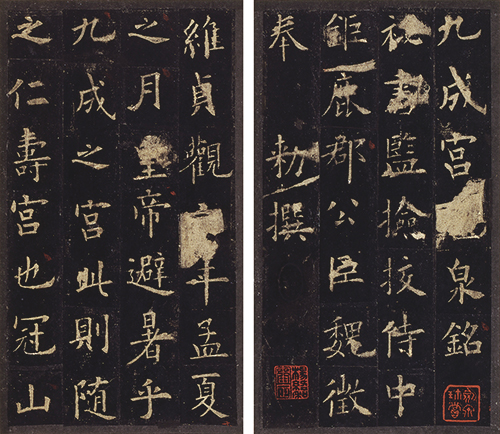

Inscription on Stele at Sweet Spring, Jiucheng Palace

By Ouyang Xun

Tang dynasty, dated 632

Taito City Calligraphy Museum, Tokyo

By Ouyang Xun

Tang dynasty, dated 632

Taito City Calligraphy Museum, Tokyo

|

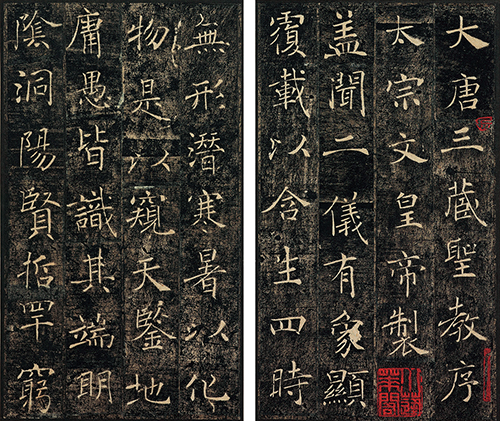

Inscriptions on Yanta Pagoda Steles

By Chu Suiliang

Tang dynasty, dated 653

Tokyo National Museum

By Chu Suiliang

Tang dynasty, dated 653

Tokyo National Museum

|

(detail) |

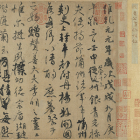

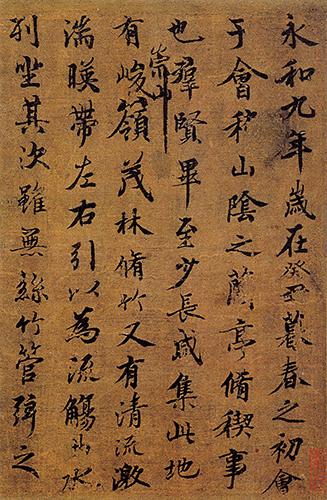

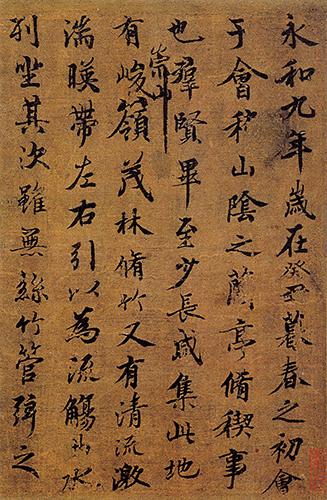

Preface to the Lanting Pavilion, Yellow-silk Version

Copied by Chu Suiliang, original: by Wang Xizhi

Tang dynasty, 7th century

On long-term loan to the National Palace Museum, Taipei

|

PageTop

Chapter Three | Calligraphy of the Tang Dynasty: Yan Zhenqing

― The Decline of Wang Xizhi’s Writing Style and the Emergence of Emotional Expression ―

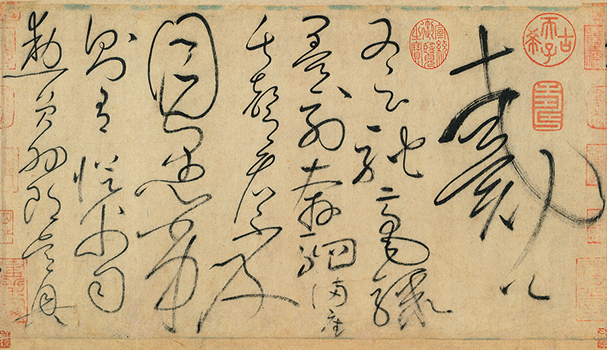

Emperor Xuanzong became the sixth Tang emperor in 712. He was very fond of the magnanimous grandeur of clerical script. The voluptuous flamboyance of this script influenced other writing styles and it revolutionized the written form. Calligraphers were no longer bound by tradition and they would now express their feelings without reserve. Zhang Xu would get drunk and then wield the brush while shouting, for example, but his works still received high acclaim and his style was inherited by the monk Huaisu.

The Tang period underwent drastic changes as a result of the Anshi Rebellion. Not only did Yan Zhenqing help to save the imperiled Tang dynasty, he also reflected the changing consciousness of the times to brilliant effect in his calligraphy. With its roots in the writing styles of Chu Suiliang and others, standard script now engendered a new way of writing known as "Yan style." This was characterized by powerful brush strokes and a sense of profundity, and it later became the basis for the Mincho ("Ming-style") typeface.

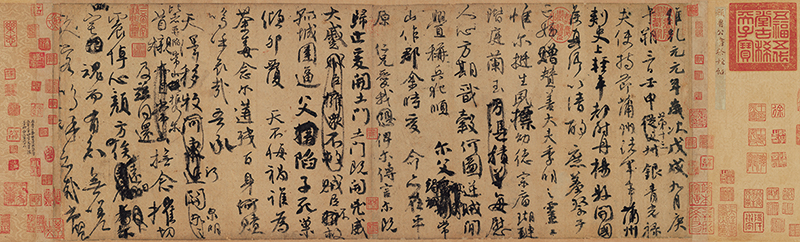

After his nephew, Yan Jiming, died a violent death during the Anshi Rebellion, a heartbroken Yan Zhenqing wrote Draft of a Requiem to My Nephew, a masterpiece that bears comparison with Wang Xizhi's Preface to the Lanting Pavilion. The latter work only survived for 296 years, but Draft of a Requiem to My Nephew is still with us after 1,261 years and it continues to move many people to this day.

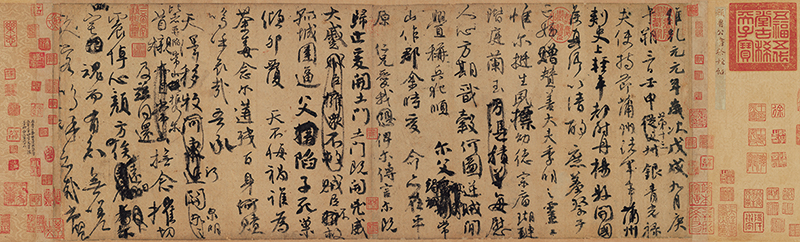

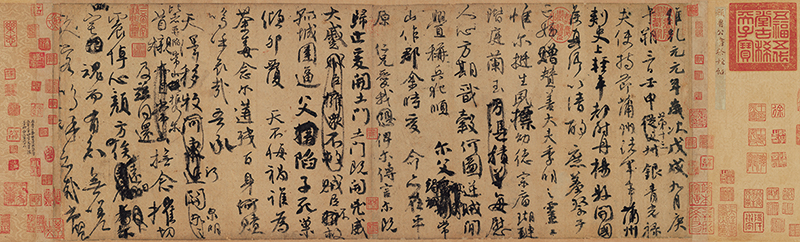

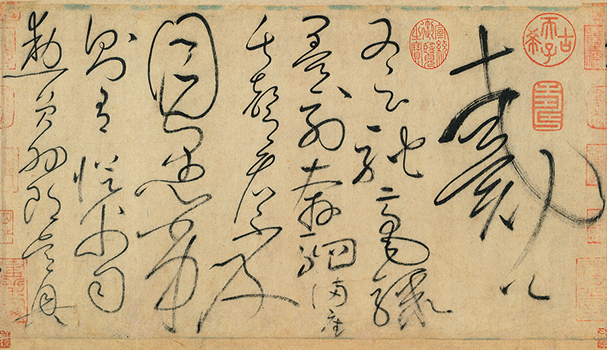

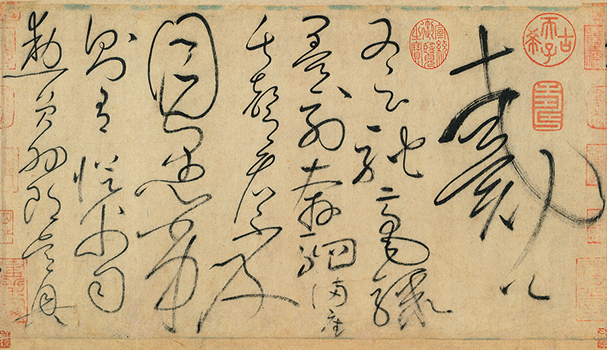

On Exhibit for the First Time in Japan!

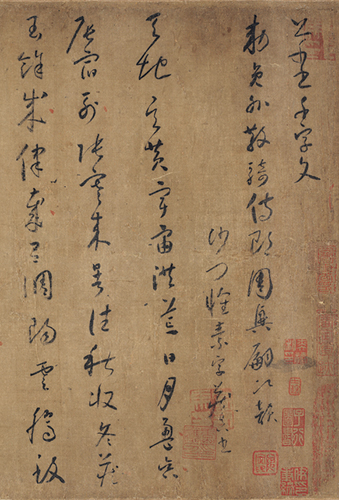

Draft of a Requiem to My Nephew

By Yan Zhenqing

Tang dynasty, dated 758

National Palace Museum, Taipei

This is the draft of a requiem for Yan Zhenqing’s nephew, Yan Jiming. Yan Zhenqing wrote this masterpiece when he was 50. It is infused with grief for his nephew, who died young during the Anshi Rebellion, as well as hatred for the rebel leader An Lushan and the traitorous Wang Chengye.

|

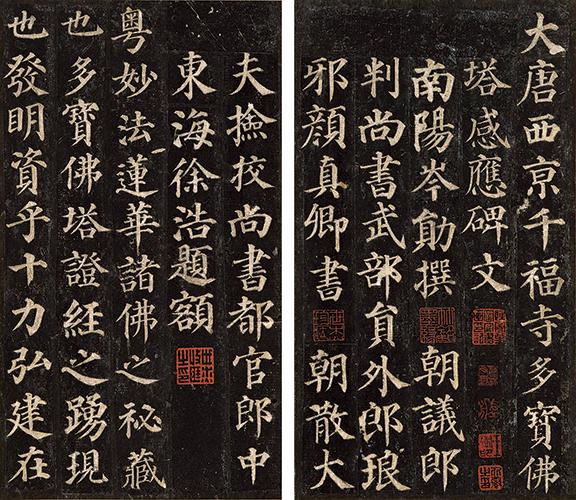

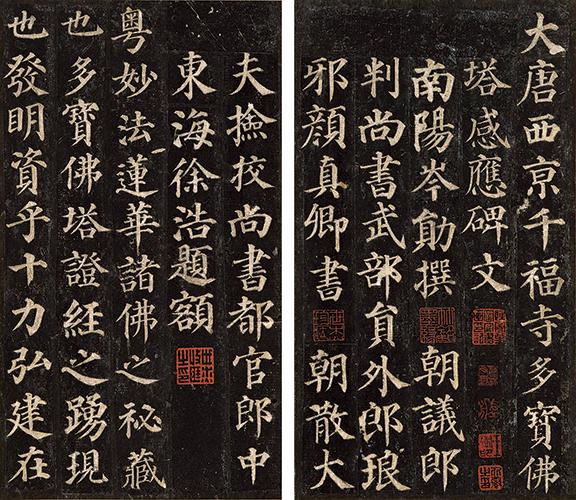

Inscription on Stele of Duobao Pagoda of Qianfusi Temple

By Yan Zhenqing

Tang dynasty, dated 752

Tokyo National Museum

|

On Exhibit for the First Time in Japan!

(detail) |

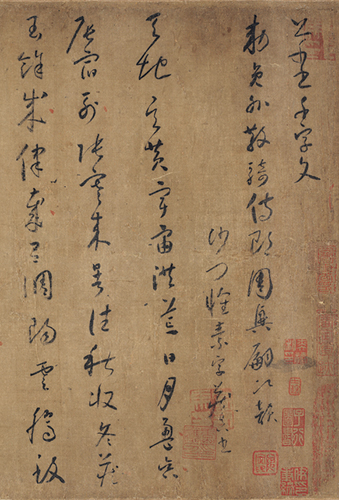

Autobiography

By Huaisu

Tang dynasty, dated 777

National Palace Museum, Taipei

|

(detail) |

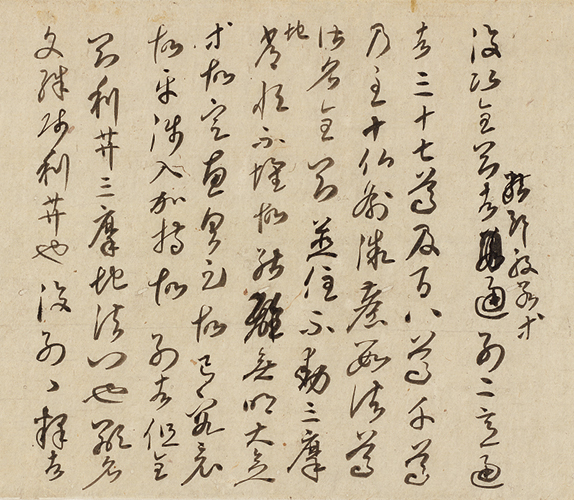

Thousand-character Essay in Small Cursive Script, Known as Qianjin Tie

By Huaisu

Tang dynasty, dated 799

On long-term loan to the National Palace Museum, Taipei

|

PageTop

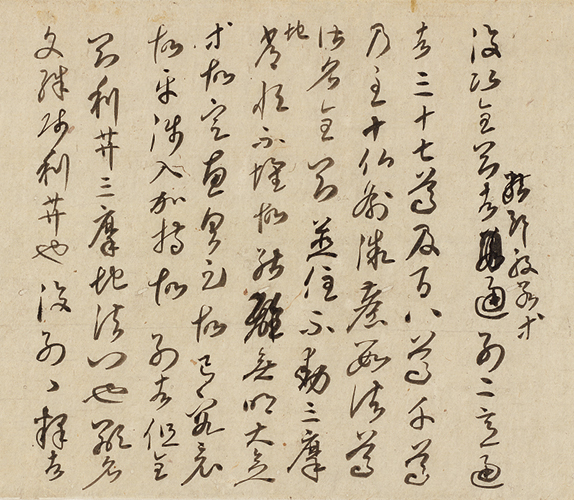

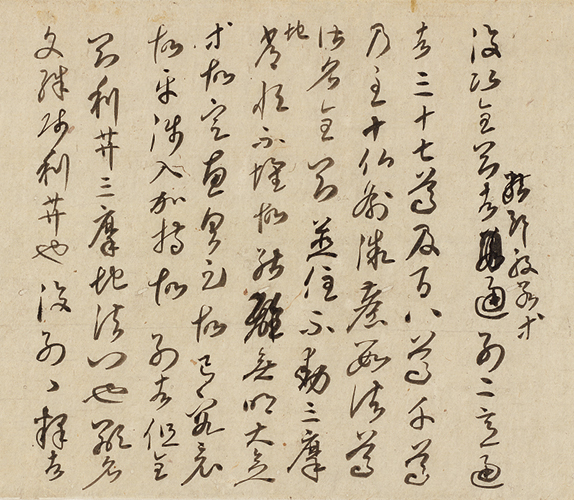

Chapter Four | The Reception of Tang-dynasty Calligraphy in Japan

― The Sanpitsu and Sanseki ―

Tang-dynasty calligraphy arrived on Japan's shores during the Nara period. The influence of Ouyang Xun's writing style can be seen in the Kongo Jodarani Kyo Sutra, while Zasshu ("Miscellaneous Works") by Emperor Shomu clearly owes a debt to Chu Suiliang. However, calligraphy by Wang Xizhi was particularly treasured in the capital of Nara. His influence is evident in a number of extant works from that time, including Empress Komyo's Gakki-ron, the original of which was the rubbing of an essay on Yue Yi (Yue Yi Lun) by Xizhi, and several reproductions of his penmanship by sutra copyists. Priest Kukai and Tachibana no Hayanari are known as two of the Sanpitsu ("Three Brushes"), the collective name given to three master calligraphers from Japan's Heian period. The two men traveled to Tang-dynasty China with the priest Saicho and a Japanese envoy. While there, they studied works by Wang Xizhi and the Four Great Calligraphers of the Tang dynasty. Kukai's style is particularly indebted to Wang Xizhi and other Tang calligraphers. Emperor Saga was also one of the Sanpitsu. He was friends with Kukai and his writing style was influenced by Ouyang Xun.

Japanese envoys to China were discontinued during the mid-Heian period, with the Tang dynasty coming to an end in 907. However, the influence of Wang Xizhi lived on through Ono no Michikaze and Fujiwara no Yukinari. These two men were part of a second group of great Japanese calligraphers known as the Sanseki ("Three Brush Traces") and they were instrumental in forming a uniquely-Japanese calligraphic style based on Xizhi's works. Fujiwara no Sukemasa was the third Sanseki. His calligraphy is marked by a freewheeling boldness reminiscent of Huaisu's "wild cursive" style.

(detail) |

Segment of Commentary on the Diamond Sutra (Kongo Han’nya Kyo)

By Kukai

Heian period, 9th century

Kyoto National Museum

(National Tresure)

|

PageTop

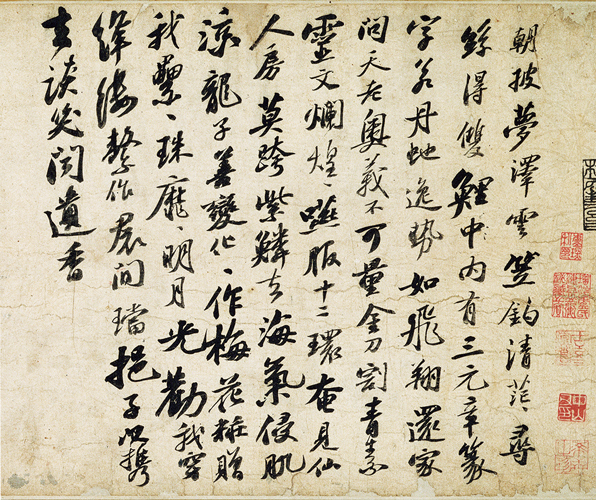

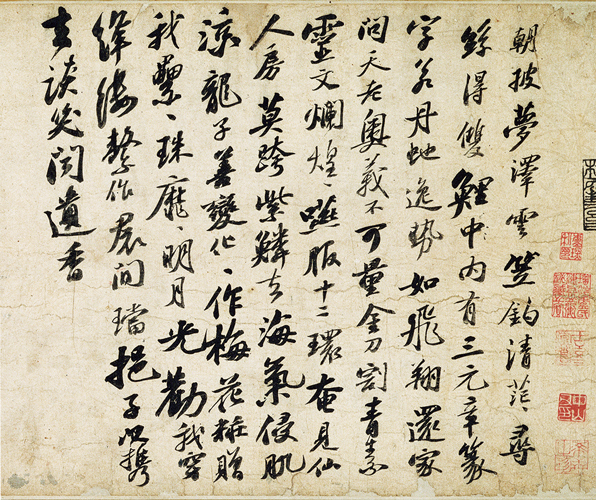

Chapter Five | The Appreciation of Yan Zhenqing in the Song Dynasty

― The Veneration of Humanity and the Pursuit of Ideals ―

Yan Zhenqing created his own unique writing style. While this was based on earlier traditions, it still took time before it found wider acceptance in society. Zhenqing's name was not even included on the list of contemporary calligraphers in Shushu fu, an eminent treatise on calligraphy from the latter half of the 8th century that records the history of calligraphy from the Zhou to the Tang dynasty.

However, the winds of change started to blow entering the Song dynasty. Zhenqing's writing style reflected the feelings that sprang up around the time of the Anshi Rebellion. It was inherited and further developed by intellectuals during the Song dynasty. Ouyang Xiu held Zhenqing in particularly high regard. Xiu evaluated works of calligraphy according to the calligraphers' personality and sense of humanity. In this sense, he regarded Zhenqing's works as the calligraphic ideal. Cai Xiang also adored Zhenqing's calligraphy and produced several works in the style of Zhenqing.

Without doubt, however, Su Shi was Zhenqing's biggest admirer and devotee. Su Shi commented that Zhenqing's calligraphy was exceptionally powerful. He also said it was similar to Du Fu's poetry in the way it overturned convention. This way of thinking was taken on board by Huang Tingjian, while Mi Fu also had a high regard for Zhenqing's running script.

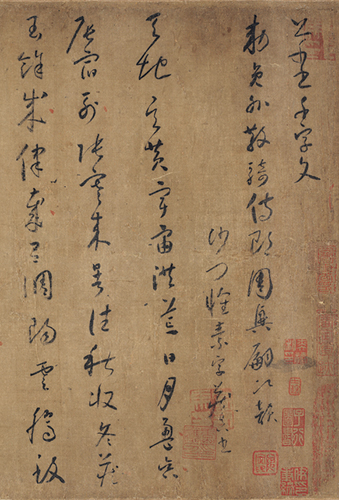

(detail) |

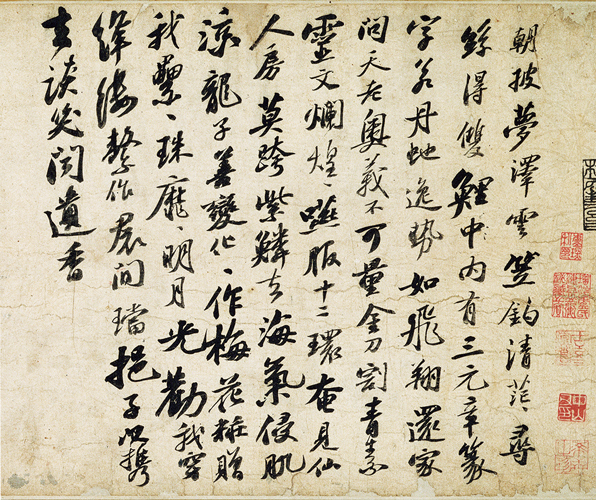

Poems by the Immortal Li Bai in Running Script

By Su Shi

Northern Song dynasty, dated 1093 Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

(Important Cultural Properties)

|

PageTop

Chapter Six | The Influence on Later Generations

― The Collapse of Wang Xizhi’s Legendary Status ―

Original works by Wang Xizhi all but disappeared from the Tang to the Song dynasty, with his calligraphy attaining near legendary status through the diffusion of copybooks. In the Yuan dynasty, Zhao Mengfu revived a traditional style of writing based on Xizhi's calligraphy. In the Ming dynasty, meanwhile, Dong Qichang developed a novel style that emphasized the expression of feeling. In this way, the balance between traditional and novel styles ebbed and flowed according to the tastes and fashions of the times.

During the Qing dynasty, the traditional copybook school of learning faced skepticism as the 19th century approached. There was a growing sense that the copybooks were becoming far removed from Xizhi's original writings after endless reproductions. Instead, people began to study inscriptions on stone monuments as authentic sources of ancient calligraphy, with the so-called stele school now displacing the copybook school as the prominent school in calligraphy.

Zhao Zhiqian originally studied works by Yan Zhenqing. However, he later inclined toward the stele school and established a rustic style of writing based on an aesthetic sensibility at complete odds with traditional forms of calligraphy based on Wang Xizhi's works. Zhao Zhiqian's emergence ultimately demolished the legend of Wang Xizhi. The Qing dynasty saw the blooming of a diverse range of writing styles, but the calligraphic beauty cultivated during the Tang dynasty has not faded and it continues to shine radiantly to this day.

|

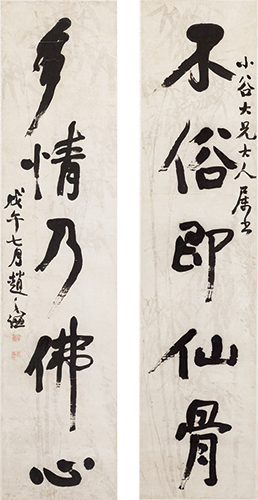

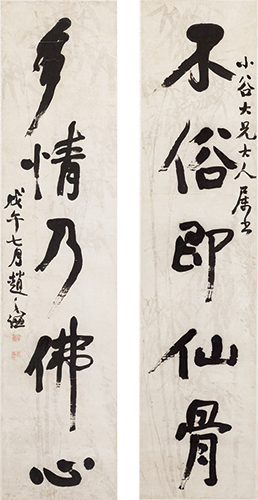

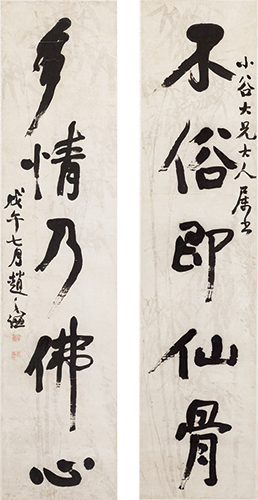

Couplet of Five-character Phrases in Running Script

By Zhao Zhiqian

Qing dynasty, dated 1858

Private collection

|

PageTop