Highlights of the Exhibition

Part 1: Tea of the Ashikaga Shogunate—Karamono as Adornment and the Taste for “Chinese Pieces”

It is believed that the custom of tea drinking began to fully permeate Japanese culture around the 12th century. The method of drinking powdered tea, or matcha, was brought from Song-dynasty China, to Japan as a new culture primarily by Buddhist monks who traveled frequently back and forth. Once in Japan, this tradition gradually spread among the upper-class samurai and aristocratic families.

By the Muromachi period, all the most powerful people were collecting imported art objects known as karamono (“Chinese pieces”). Decorating rooms and enjoying tea with them became grand displays of authority and power. In particular, the highest-class karamono objects were assembled in the hands of the Ashikaga shogunate, who held political dominance at the time. These objects were classified and evaluated by the doboshu advisors who were in charge of curating and appraising their collections. This value system, which reached even to tea utensils, came to have a major impact on later chanoyu culture.

Drawing from documentation found in sources such as the Kundaikan socho ki (Manual of the Attendant of the Shogunal Residence), Muromachi-dono gyoko okazari ki (Record of the Objects Displayed in Muromachi Palace), and other texts, this section focuses on the masterpieces of Chinese painting and Chinese objects from the Ashikaga shogunal collection, known as the Higashiyama Gomotsu, that were most highly esteemed in the discerning eyes of these appraisers.

Plum Blossoms and Pair of Sparrows, Attributed to Ma Lin (Ba Rin)

Southern Song dynasty, 13th century, China

Important Cultural Property

Tokyo National Museum

[on exhibit from April 25 to May 21, 2017]

Tea Bowl, Yohen (“kiln-changed”) tenmoku, type, Known as the Inaba tenmoku

Southern Song dynasty, 12th–13th century, China

National Treasure

Seikado Bunko Art Museum, Tokyo

[On exhibit through May 7, 2017]

Flower Vase, Celadon glaze, Shimokabura (“turnip-bottom”) type

Southern Song dynasty, 13th century, China

National Treasure

Foundation Arc-en-Ciel, Tokyo

Page top

Part 2: The Birth of Wabicha—Objects to Satisfy the Heart

By the end of the 15th century, with the approaching decline of the Ashikaga shogunate, the townsman class, who were to become the sustaining force of culture in the new age, rapidly gained power and began to enjoy and master arts such as renga poetry and Noh theater, tea, flowers, incense, and other pursuits that had until then been the exclusive domain of the upper classes.

As the range of people who gained a taste for chanoyu expanded, the places and spaces for the enjoyment of chanoyu began to change, and major transformations in the utensils became evident. While warring-state generals and wealthy merchants competed to attain first-class karamono (“Chinese pieces”) formerly included in the Higashiyama Gomotsu or the Ashikaga shogun family collection, a new taste was emerging at the same time. Murata Shuko (1423–1502), a tea master trained in Zen practice, and others known as the “Shimogyo” (lower Kyoto) tea people, came to discover objects that suited their own hearts not only among karamono objects but also in the midst of their everyday lives. By integrating the use of these kinds of utensils, tea of refined and humble style, known as wabicha, was born. This spirit was taken up by the wealthy Sakai merchant Takeno Jo’o (1502–55) and spread further, taking root deeply among the townspeople.

This section traces the shift in the values towards chanoyu utensils, from karamono to koraimono (Korean pieces) and wamono (Japanese pieces), through the eyes of the warlords and tea masters who lived during the 15th–16th centuries, by exhibiting the arts of wabicha that germinated in this transitional period.

Tea Caddy, Katatsuki (“shouldered”) type, Known as Hatsuhana (“first flowers of spring”)

Southern Song to Yuan dynasty, 13th–14th century, China

Important Cultural Property

Tokugawa Memorial Foundation, Tokyo

[On exhibit through April 23, 2017]

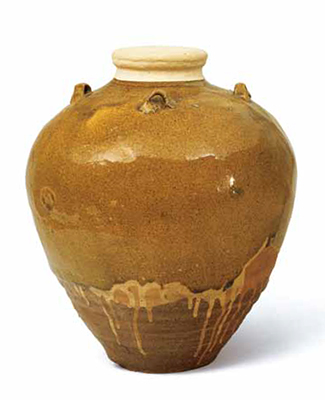

Tea Leaf Jar, Known as Shoka (“pine flowers”)

Southern Song to Yuan dynasty, 13th–14th century, China

Important Cultural Property

Tokugawa Art Museum, Aichi

[On exhibit through May 7, 2017]

Tea Bowl, Amamori (“rain-dripping”) type

Joseon dynasty, 16th century, Korea

Important Cultural Property

Nezu Museum, Tokyo

Page top

Part 3: The Perfection of Wabicha—Sen no Rikyu and his Time

In the Azuchi-Momoyama period, wabicha achieved greatness with Sen no Rikyu (1522–91). Chanoyu ultimately came to permeate more broadly and deeply, spreading from the powerful rulers to the daimyo warrior class and further to the townspeople.

Rikyu was born into a prominent merchant family in Sakai and became familiar with tea from a young age. His transcendent eye and superb sense in coordinating utensils led to his promotion as tea advisor to Oda Nobunaga (1534–82), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–98), and other powerful leaders. Rikyu not only carried on the tradition of Shuko, the original founder of wabicha, but he also pursued his own ideals, creating new utensils and perfecting his own refined tea style. This spirit had a major influence on his top disciple Furuta Oribe (1544–1615) and other tea masters who followed, forming the cornerstone of chanoyu as it is practiced today.

This section first introduces utensils associated with Rikyu in the two categories of objects “selected by Rikyu” and objects “created by Rikyu.” In addition, it looks at tea practice after Rikyu’s death and examines the tea of the samurai warriors who lived in the transitional period from the Azuchi-Momoyama to the Edo period, with particular focus on the three tea masters Furuta Oribe, Oda Uraku (Nagamasu, 1548–1622), and Hosokawa Sansai (Tadaoki, 1563–1614).

Tea Bowl, Aka (red) raku type, Known as Muichimotsu (“with nothing”)

By Chojiro

Azuchi-Momoyama period, 16th century

Important Cultural Property

Egawa Museum of Art, Hyogo

[On exhibit through May 7, 2017]

Tea Bowl, Koido type, Known as Roso (“old monk”)

Joseon dynasty, 16th century, Korea

Fujita Museum, Osaka

[On exhibit through April 23, 2017]

Tea Bowl, Shino type, Known as Unohanagaki (“deutzia shrubs”)

Azuchi-Momoyama – Edo period, 16th–17th century

National Treasure

Mitsui Memorial Museum, Tokyo

Page top

Part 4: Classical Revival—The Tea of Kobori Enshu and Matsudaira Fumai

In the Edo period, chanoyu experienced various changes as society entered a period of peace and tranquility. The Tokugawa shogunate government and surrounding daimyo warrior-class families, led by Kobori Enshu (1579–1647) in particular, tried to revive the warrior-class tea tradition originated by the Ashikaga shogunate. Another movement arose to institute an iemoto headmaster system that established a line of succession for Rikyu’s tea, and yet another movement created a new style of tea that incorporated the elegant world of aristocratic culture. These various traditions exerted considerable influence on each other.

This section presents tea objects of the first half of the Edo period with special focus on utensils associated with Kobori Enshu, who revived the tea tradition of the warrior class and formulated a new style of elegant simplicity, known as kirei-sabi, that revived the spirit of Heian aristocratic culture.

Also, it introduces utensils associated with Matsudaira Fumai (1751–1818), the daimyo lord of the Matsue domain who followed in Enshu’s footsteps and looked back to the classics, collecting great masterpieces with a keen eye and working to reorganize and resuscitate chanoyu in the later Edo period. Finally, it also features masterpieces owned by noted wealthy merchant families of the Edo era, such as the Mitsui, Konoike, and Sekido, who developed their own unique styles of chanoyu while deepening their connections with the Sen lineage.

Tea Bowl, Koido type, Known as the Rokujizo

Joseon dynasty, Korea

Sen-oku Hakuko Kan, Kyoto

[On exhibit from April 25, 2017]

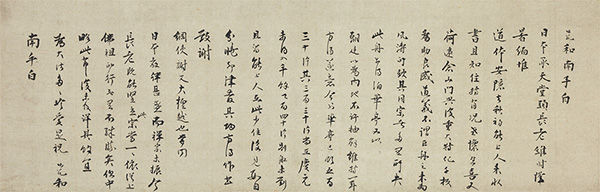

Letter of Thanks for a Gift of Boards

By Wuzhun Shifan (

Mujun Shihan)

Southern Song dynasty, dated 1242(Chunyou 2), China

National Treasure

Tokyo National Museum

[On exhibit from May 23, 2017]

Tea Bowl, Kohiki (“powdery”) type, Known as the Miyoshi kohiki

Joseon dynasty, 16th century, Korea

Important Cultural Property

Mitsui Memorial Museum, Tokyo

[on exhibit from February 14 to March 12, 2017]

Page top

Part 5: The Eye of the Early Modern Tea Connoisseur

From the end of the Edo period to the Meiji era, at the time of drastic political change in Japan, many treasured objects and tea utensils from temple holdings and old family collections were released onto the market. Amidst this time of upheaval, notable industrialists such as Hirase Roko (1839–1908), Fujita Kosetsu (1841–1912), Masuda Donno (1848–1938), Hara Sankei (1868–1939) and others with the fortune and the eye were able to collect chanoyu utensils, and amassed major collections.

They studied the traditional history of chanoyu and at the same time also integrated new perspectives, bringing masterpieces of ancient calligraphy and Japanese-style yamato-e painting, Buddhist paintings, and other types of Japanese art into tea rooms. Hosting tea gatherings for important personalities from a variety of social circles, they contributed to widely expanding the reach of chanoyu.

The eye and the aesthetic of these important men of the Taisho to Showa eras were further passed on to connoisseurs of the next generation, such as Hatakeyama Sokuo (1881–1971). Now, the spirit and richly individualistic aesthetic sensibilities of these early modern connoisseurs has been entrusted to the various museums that continue to preserve precious chanoyu collections and make them accessible to the public today.

Through the collections of these five connoisseurs whose names are widely known respectively in Japan, this section presents representative masterpieces from each collection, for a re-appreciation of the appeal of chanoyu, which could even be considered the essence of Japanese culture itself.

Stacking Tea Bowls, Gold and silver, Lozenges design in overglaze enamels

By Nonomura Ninsei

Edo period, 17th century

Important Cultural Property

MOA Museum of Art, Shizuoka

[on exhibit from May 9 to May 21, 2017]

Incense Container, Large tortoise shape, Cochin type

Ming dynasty, 17th century, China

Fujita Museum, Osaka

[On exhibit through April 23, 2017]

Page top