平成館 特別展示室

2024年1月16日(火) ~ 2024年3月10日(日)

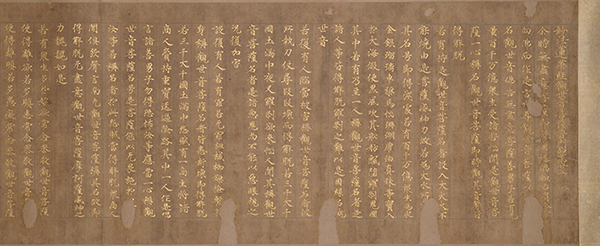

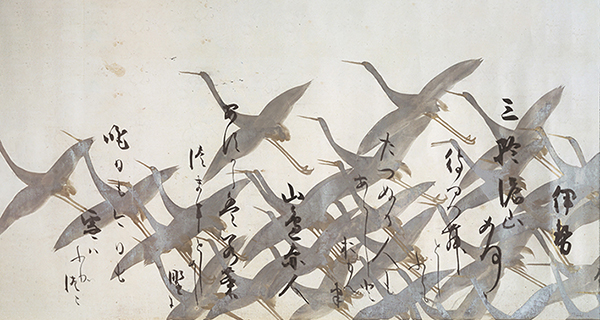

本阿弥光悦(ほんあみこうえつ・1558〜1637)は戦乱の時代に生き、さまざまな造形にかかわり、革新的で傑出した品々を生み出しました。それらは後代の日本文化に大きな影響を与えています。しかし光悦の世界は大宇宙(マクロコスモス)のごとく深淵で、その全体像をたどることは容易ではありません。

そこでこの展覧会では、光悦自身の手による書や作陶にあらわれた内面世界と、同じ信仰のもとに参集した工匠たちがかかわった蒔絵など同時代の社会状況に応答した造形とを結び付ける糸として、本阿弥家の信仰とともに、当時の法華町衆の社会についても注目します。造形の世界の最新研究と信仰のあり様とを照らしあわせることで、総合的に光悦を見通そうとするものです。

「一生涯へつらい候事至てきらひの人」で「異風者」(『本阿弥行状記』)といわれた光悦が、篤い信仰のもと確固とした精神に裏打ちされた美意識によって作り上げた諸芸の優品の数々は、現代において私たちの目にどのように映るのか。本展を通じて紹介いたします。

【開館時間延長のお知らせ】

特別展「本阿弥光悦の大宇宙」は、2月16日(金)以降、金・土曜日の開館時間を19時00分まで延長します(入館は18時30分まで)。

(注)総合文化展もあわせてご覧いただけます。

(注)建立900年 特別展「中尊寺金色堂」の開館時間は別途ご確認ください。