展覧会のみどころ

桃山の精髄―天下人の造形

室町時代末期から江戸時代初期にかけての京の移り変わる姿を描いた「洛中洛外図屛風」をプロローグとして、狩野永徳や長谷川等伯に代表される安土桃山時代の画家たちによる豪壮華麗な障屛画、志野や織部に代表される意匠性優れた桃山茶陶、戦場でひときわ目立つ戦国武将の甲冑、高台寺蒔絵や世界へと視野を広げた南蛮美術など、安土桃山時代を特徴づける美術作品の数々によって、天下人が夢を追い求めた黄金の時代の造形が並びます。

後期展示

唐獅子図屛風

狩野永徳筆 安土桃山時代・16世紀 宮内庁三の丸尚蔵館蔵

縦2メートル20センチを超す巨大な屛風に、金地金雲を背景として2頭の唐獅子がゆっくりと歩む。周囲を威圧するような姿は、時代の空気を体現していった狩野永徳の、そして桃山絵画の代表作です。

|

|

|

|

前期展示

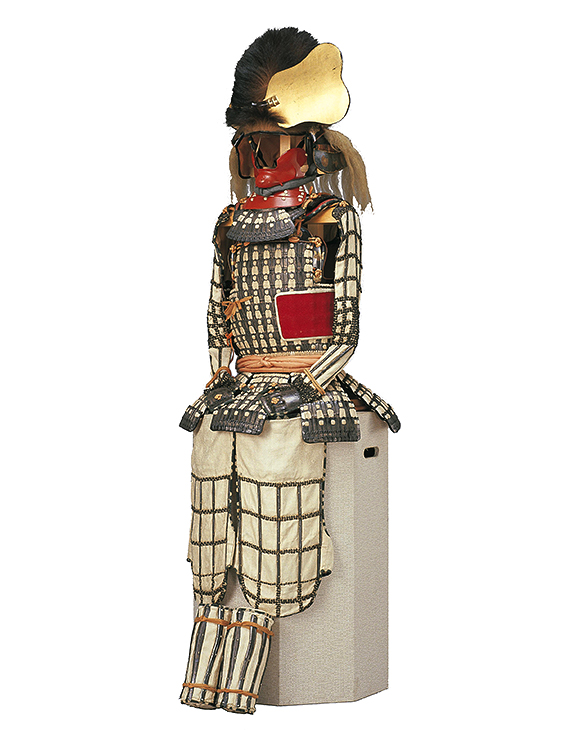

重要文化財 銀伊予札白糸威胴丸具足

安土桃山時代・16世紀 宮城・仙台市博物館蔵

伊達政宗が豊臣秀吉より拝領した甲冑で、全身の防具を揃いの仕立てに誂える「当世具足」の形式が整いつつあったころの名品です。

|

|

|

前期展示

重要文化財 花鳥蒔絵螺鈿聖龕

安土桃山時代・16世紀 九州国立博物館蔵

欧州に輸出されたキリスト教の祭儀具として、国内の遺品中最大かつ最高の豪華さを誇る作例。漆の技が、聖画を見事に荘厳しています。

|

|

|

(右隻部分) (右隻部分)前期展示

国宝 洛中洛外図屛風 (上杉家本)

狩野永徳筆 室町時代・永禄8年(1565) 山形・米沢市上杉博物館蔵

織田信長が、上杉謙信に贈ったとされる京の都を描いた屛風。狩野永徳が23歳で描いたとされ、天を突くように伸びる建物の屋根、金雲の間に見え隠れする色鮮やかな景物が、都の活気を伝えています。

|

前期展示

国宝 檜図屛風

狩野永徳筆 安土桃山時代・天正18年(1590) 東京国立博物館蔵

天正18年(1590)、秀吉の命により建てられた八条宮(後の桂宮家)邸を飾った襖絵。信長、秀吉に好まれ桃山画壇を牽引していった狩野永徳の力強い描写が辺りを威圧するような生命感にあふれています。

|

通期展示

国宝 楓図壁貼付

長谷川等伯筆 安土桃山時代・文禄元年(1592)頃 京都・智積院蔵

秀吉が、3歳で夭折した長男鶴松の菩提を弔うために建立した祥雲寺(しょううんじ)(現在の智積院(ちしゃくいん))の襖絵。狩野永徳の大画様式にもとづきながら叙情性が加えられています。

|

です

変革期の100年―室町から江戸へ

室町時代末期から江戸時代初期にかけての100年の間に、美術の表現はどのように変わっていったのかを比較しながらご覧いただきます。天皇や織田信長、豊臣秀吉、徳川家康の書、室町幕府第13代将軍・足利義輝から家康までの肖像画、同じテーマで描かれた絵画、貨幣や鏡などを比較しながら見ることで、移り変わる時代意識と美術表現の関係を感じ取ることができます。

|

|

|

後期展示

重要文化財 足利義輝像

伝土佐光吉筆 策彦周良賛

安土桃山時代・天正5年(1577)

国立歴史民俗博物館蔵

室町幕府第13代将軍・足利義輝の13回忌に描かれた遺像。宮廷の仕事を務めた土佐派の画家土佐光吉(とさみつよし)が描いたと考えられており、上部には入明した臨済僧・策彦周良(さくげんしゅうりょう)の賛があります。

|

|

|

通期展示

重要文化財 豊臣秀吉像画稿

伝狩野光信筆 安土桃山時代・16世紀

大阪・逸翁美術館蔵

狩野永徳の長男・狩野光信(かのうみつのぶ)が描いたとされる「豊臣秀吉像」の下絵。顔の「紙形」(スケッチ)が貼られ、「これがよくに(似)申よし、きい(貴意)にて候」と記されています。

|

|

|

桃山前夜―戦国の美

きらびやかで力強いといわれる桃山文化ですが、その土台は室町時代に築かれました。禅宗寺院の大画面障壁画、京を描いた洛中図、輸出品として人気を博した金屛風の数々。それまで天皇や将軍などを中心に儀礼と格式を重んじ展開されていた文化活動は、応仁の乱を契機に各地の戦国大名へと広がり、彼らの志向を加味する形で変化していきます。本章では室町時代末期の古典的な美の姿を確認しつつ、やがて訪れる桃山文化への萌芽を探ります。

(右隻) (右隻)展示期間:11月10日(火)~11月29日(日)

重要文化財 四季花鳥図屛風

狩野元信筆 室町時代・天文19年(1550) 兵庫・白鶴美術館蔵

狩野派による金屛風のうち、制作年が明らかな最古例のひとつ。画中に作者の狩野元信(かのうもとのぶ)(1477~1559)自身による生年入りの落款があります。

|

茶の湯の大成―利休から織部へ

覇を競う武将たちや富を得た町衆が、こぞって「名物」と呼ばれる高価な茶湯道具を求めた時代。そこにあらわれたのが、天下人織田信長、豊臣秀吉の茶頭をつとめた千利休(せんのりきゅう)(1522~91)でした。利休は流行にとらわれることなく、自らの眼で心にかなう道具を選び、新たな道具をつくり出します。唐物や名物を第一とする風潮に鋭く厳しい姿勢で切り込んだのです。こうした利休の精神は、古田織部(ふるたおりべ)(1544~1615)ら後継の人びとに大きな影響を与えていきました。本章では天正から慶長年間にいたる時期に注目し、利休と織部ゆかりの名品、そして激動の時代をたくましく生きた人びとの心を映すような力強い造形が魅力の「桃山茶陶」をえりすぐって紹介します。

|

|

|

展示期間:10月27日(火)~11月29日(日)

重要文化財 黄瀬戸立鼓花入 銘 旅枕

美濃 安土桃山時代・16世紀

大阪・和泉市久保惣記念美術館蔵

美濃で焼かれた黄瀬戸の茶陶を代表する逸品であり、茶の湯の大成者千利休が所持したことでも知られます。素朴ながら力強い姿と流れる釉の景色に滋味があふれています。

|

桃山の成熟―豪壮から瀟洒へ

豊臣秀吉に重用され画壇を牽引していった狩野永徳の威圧的な絵画表現は、戦国武将たちに好まれ、安土桃山時代の絵画様式そのものとなりましたが、後継者たちは、力を誇示する豪放さから離れ、優美で自然な調和を重んじた美の世界を作り出していきます。自由奔放な近衞信伊(このえのぶただ)から俵屋宗達下絵による本阿弥光悦(ほんあみこうえつ)への書の展開にも同じことが言えます。やきものもまた、偶然性のある力強い造形からデザインされた美しさへと進んでいきます。人々がいきいきと暮らし、傾奇者(かぶきもの)が闊歩する姿を主題として風俗画が誕生したのもこの時代でした。

(左隻) (左隻)展示期間:10月6日(火)~10月25日(日)

重要文化財 豊国祭礼図屛風

岩佐又兵衛筆 江戸時代・17世紀 愛知・徳川美術館蔵

慶長9年(1604)8月に行われた秀吉7回忌の臨時祭礼の情景を描いたもの。豊国神社と方広寺大仏殿(ほうこうじだいぶつでん)を背景として、秀吉を追慕し、祭りを楽しみ熱狂する人々の様子が描かれています。

|

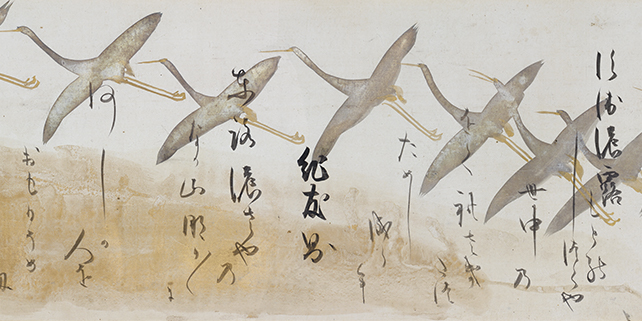

(部分) (部分)前期展示

重要文化財 鶴下絵三十六歌仙和歌巻

[書] 本阿弥光悦筆 [絵] 俵屋宗達筆 江戸時代・17世紀 京都国立博物館蔵

大胆に描かれた鶴の群れ。そこに和歌を配置するのは、光悦の腕の見せどころです。桃山美術の到達点を示す、光悦と宗達の合作です。

|

(左隻) (左隻)通期展示

国宝 花下遊楽図屛風

狩野長信筆 江戸時代・17世紀 東京国立博物館蔵

幔幕など黒色の彩色が目立ちますが、これは銀が黒変したもの。着物にも銀が多用され、当初は描かれた紙の白さとともに、すっきりとした明るい画面でした。時代の転換期らしく、傾奇者の風俗も描かれています。

|

武将の装い―刀剣と甲冑

桃山時代は常に戦闘があった厳しい時代ともいえます。それゆえ、打刀(うちがたな)や当世具足(とうせいぐそく)が普及するなど、生死を決する刀剣や甲冑は新たな展開を見せ、これまでにない武器や武具が流行しました。また、実用性だけではなく、さまざまな装飾や工夫で地位や風格のある表現が加えられ、江戸時代になると武家の格式を象徴するものとして受け入れられていきました。本章では、単なる華やかさや奇抜さでは片づけられない、武将たちの「生死をかけた装い」をご紹介します。

|

|

通期展示

重要文化財 紺糸威南蛮胴具足

安土桃山~江戸時代・16~17世紀 東京国立博物館蔵

関ヶ原の合戦の直前、徳川四天王のひとり榊原康政(さかきばらやすまさ)が家康から拝領した甲冑です。兜と胴はヨーロッパの甲冑を参考にしたものです。

|

|

|

|

|

|

通期展示

重要文化財 刀 無銘 伝元重・朱漆打刀

(刀身)伝備前元重 南北朝時代・14世紀

(刀装)安土桃山~江戸時代・16~17世紀

東京国立博物館蔵

徳川家康の次男・結城秀康(ゆうきひでやす)が用いた指料(さしりょう)で、刀装は色彩的な鮮やかさと丁寧なつくりが融合して、品格のある華麗さが生まれています。

|

泰平の世へ―再編される権力の美

大坂夏の陣で豊臣氏を滅ぼした徳川家康のもとで、元和元年(1615)、戦乱の時代は終わりを告げます。文化や美術は、一朝一夕に変わるものではない一方で、確実に時代の変化を反映しています。ここでは、江戸時代の武家の美術が、桃山美術の表現を母体としながら、室町時代の伝統的価値観を再編した徳川幕府の秩序にもとづいて誕生したことを、二条城大広間の襖絵をはじめとした、格式高い作品によってご覧いただきます。

(部分) (部分)通期展示

重要文化財 松鷹図襖・壁貼付

狩野山楽筆 江戸時代・寛永3年(1626) 京都市(元離宮二条城事務所)蔵

徳川家の京都での居城、二条城二の丸御殿の中心に位置し、公式の対面や儀式が行われた大広間を飾る長大な障壁画。近年、狩野永徳が創始した豪壮な様式を受け継いで、永徳の弟子狩野山楽(かのうさんらく)が描いた可能性が指摘されました。

|

特別展「桃山―天下人の100年」

特別展「桃山―天下人の100年」