創刊記念『國華』130周年・朝日新聞140周年 特別展「名作誕生-つながる日本美術」

-

重要文化財 仙人掌群鶏図襖(部分) 伊藤若冲筆 江戸時代・18世紀 大阪・西福寺蔵

1089ブログ「特別展『名作誕生-つながる日本美術』」 展覧会の見どころなどを紹介しています。

展覧会のみどころ

第1章 祈りをつなぐ

第2章 巨匠のつながり

第3章 古典文学につながる

第4章 つながるモチーフ/イメージ

第1章 祈りをつなぐ

仏像や仏画などの信仰を背景とする美術は、経典などに記されたことに基づいて造形化される一方で、特別なゆかりや革新的技法、形をもつ名作を規範として継承し、数々の名作が誕生してきました。第1章では、古代から中世へ、人々の祈りがつないだ仏像、仏画、説話画の数々を展示し、その規範と名作たる革新性に注目します。

1. 一木の祈り

天平勝宝5年(753)、中国・唐の高僧、鑑真[がんじん]とともに渡来した仏師たちは、日本の木材に着目し、一本の木から重量感あふれる仏像を彫り出しました。同時代の中国においても最新の表現だったこの木彫像につらなる仏像は、平安時代前期を通じて数多く造られ、大きな影響を残したのです。

2. 祈る普賢

『法華経』に基づいて表される白象に乗った普賢菩薩像は、9世紀半ばに慈覚大師 円仁[じかくだいし えんにん]が唐から請来した図像(現存せず)によって、新たに合掌する姿で表す潮流ができました。ここではこの「合掌普賢[がっしょうふげん]」につながる仏画とともに、信心深い女性の姿を反映した十羅刹女[じゅうらせつにょ]の名作もご堪能ください。

国宝 普賢菩薩騎象像[ふげんぼさつきぞうぞう] 普賢菩薩像は法華三昧[ほっけざんまい]を修する法華堂本尊や追善供養の本尊として、平安時代に盛んに製作されたことが記録からわかっています。本像はその優美さもさることながら、彩色や截金[きりかね]があざやかに残る木彫像の名作です。 |

国宝 普賢菩薩像[ふげんぼさつぞう] 明るくあざやかな彩色と精緻な截金[きりかね]が残る、平安仏画の代表作です。白く輝く肉身には淡い朱色の隈[くま]が施され、細部まで心と技が尽くされています。頭上には花の天蓋[てんがい]があり、大輪の花々が美しく降る様子が画中に静かな動きを与えています。 |

3. 祖師に祈る

日本に仏教を広めた祖師[そし]たちの生涯は、平安時代以降、障子絵や掛幅などの大画面に盛んに描き継がれ、法要などの場を飾りました。ここでは現存最古の祖師絵伝である「聖徳太子絵伝」(東京国立博物館蔵)ほか大画面説話画の名品を通して、絵伝と絵堂がつなぐ祖師への祈りをご覧いただきます。

第2章 巨匠のつながり

近年とくに人気の高い日本美術史上の巨匠たちもまた、海外の作品や日本の古典から学び、継承と工夫を重ねるなかで、個性的な名作を生みだしました。第2章では、雪舟、宗達、若冲という3人の「巨匠」に焦点を絞って、代表作が生まれるプロセスに迫ります。

4. 雪舟と中国

雪舟等楊(1420~1506?)は、南宋時代の夏珪[かけい]や玉㵎[ぎょくかん]など、過去の名画家の作品に学ぶだけでなく、水墨画の本場である中国へ旅し、同時代である明の画風も取り入れて、独自の水墨画を確立しました。ここでは雪舟と中国のつながりについて、実景図、山水図、花鳥図、倣古[ほうこ]図の4つのグループで見ていきます。

雪舟等楊筆 室町時代・15世紀 京都国立博物館蔵 (展示期間:4月13日(金)~5月6日(日))

室町時代の画僧・雪舟等楊は、応仁元年(1467)、47歳のときに明に渡り、足かけ3年の滞在中にさまざまな画技を吸収しました。鶴の姿態が印象的な本屛風は、画面両端に屈曲する松と梅を置き、明時代の花鳥画に学んだ画面構成の方法を駆使しています。

呂紀筆 (展示期間:4月13日(金)~5月6日(日))

呂紀[りょき](1429~1505)は明時代中期に活躍した、中国・寧波出身の宮廷画家で、写実的な着色の花鳥画を得意としました。本図は呂紀の代表作として知られています。とくに冬景図の大胆な流水や屈折する樹枝と、謹直に描かれた花や鳥との対比は、強烈な印象を残します。

5. 宗達と古典

安土桃山時代から江戸時代初期にかけて活躍した俵屋宗達(生没年不詳)は、「俵屋」という絵屋を営む町絵師でありながら、『伊勢物語』や『西行物語』など古典文学を主題とした絵画を多く描きました。ここでは扇絵と絵巻の名作を通して、宗達が学んだもの、吸収したものに着目し、その創作の源を探ります。

6. 若冲と模倣

伊藤若冲(716~1800)の作品には、既成の形かたちを再利用して新たな造形を作るという表現上の特徴があります。画風を模索していた頃には中国の宋元画を模写し、また生涯を通じて同じモチーフの同じ型かたを繰り返し描いて、独自の表現に至りました。ここでは鶴図と鶏図について宋元画の模倣と自己模倣という切り口でご覧いただきます。

|

雪梅雄鶏図[せつばいゆうけいず] 伊藤若冲筆 江戸時代・18世紀 京都・両足院蔵 (展示期間:通期展示) これから本格的に絵画制作を始めようとする比較的初期の作品で、落款から錦小路[にしきこうじ]のアトリエで制作されたことがわかります。鶏の端正な描き方、岩や雪の形に若冲独特の形態感覚を見ることができます。 |

伊藤若冲筆 江戸時代・18世紀 大阪・西福寺蔵 (展示期間:通期展示)

金地に鶏を大きく配した、お寺の本堂を飾る襖絵。異国をイメージするサボテンが描かれ、あざやかな色彩が目を引きつけます。自身で75歳と記していますが、制作年には諸説があります。若冲の描く鶏図の到達点を見ることができます。

第3章 古典文学につながる

日本を代表する古典文学である『伊勢物語』や『源氏物語』。人々の心に残る場面は、その情景を想起させる特定のモチーフの組み合わせによって工芸品に表され、広く愛されてきました。第3章では、文学作品から飛び出して連綿と継承された意匠の名品を、『伊勢物語』から「八橋[やつはし]」「宇津山[うつのやま]」「竜田川[たつたがわ]」、『源氏物語』から「夕顔[ゆうがお]」「初音[はつね]」を通してたどります。

7. 伊勢物語

平安時代初期に成立した歌物語である『伊勢物語』からは、燕子花[かきつばた]と橋を表す「八橋」、蔦の生い茂る山道を表す「蔦細道」を取り上げます。

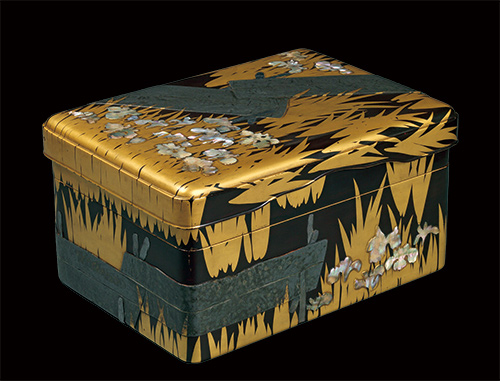

|

国宝 八橋蒔絵螺鈿硯箱 [やつはしまきえらでんすずりばこ] 尾形光琳作 江戸時代・18世紀 東京国立博物館蔵 (展示期間:4月13日(金)~5月6日(日)) 『伊勢物語』第九段の三河国八橋の情景に取材した意匠の硯箱。蓋表から身側面にかけて大胆にデザイン化した燕子花[かきつばた]と橋を表しています。花は鮑貝の螺鈿、葉は金の平蒔絵、橋は鉛板という具合に素材と技法の使い分けも絶妙です。 |

8. 源氏物語

『伊勢物語』に続き平安時代中期に成立した長編物語『源氏物語』からは、垣根に咲く夕顔と御所車を表す「夕顔」と、梅にとまる鶯を表す「初音」を取り上げます。

重要文化財 初音蒔絵火取母[はつねまきえひとりも] 六弁花形に膨らんだ様子が阿古陀瓜[あこだうり]に似るために阿古陀形と呼ばれる形式の香炉です。金の研出蒔絵[とぎだしまきえ]で梅と松、金の金貝で鶯、銀の金貝で「はつね」「幾何[きか]せよ」の文字を表しています。『源氏物語』「初音」の歌意に取材した意匠です。 |

夕顔蒔絵大鼓胴[ゆうがおまきえおおかわのどう] 『源氏物語』「夕顔」の情景に取材した意匠の大鼓の胴。平蒔絵[ひらまきえ]に絵梨子地[えなしじ]を交えて、夕顔・扇・竹垣の文様を表しています。桃山時代に流行した高台寺蒔絵[こうだいじまきえ]の技法の系譜に連なるが、高台寺蒔絵には珍しい文学意匠の作例です。 |

第4章 つながるモチーフ/イメージ

身近な自然物や人々の内面を表し今に伝わる名作たちは、すでにある名作の型や優れた技法を継承しつつ、斬新な解釈や挑戦的手法によって誕生してきました。第4章では、「山水」「花鳥」「人物」の主題と近代洋画の名作からさまざまなモチーフや型をご覧いただき、人と美術のつながりをご覧いただきます。

9. 山水をつなぐ

私たちを包む大自然の風景は、見る人の心を投影しながら技法も形もさまざまに表現されてきました。ここでは湿潤な大気に水墨の濃淡を駆使して描きつがれた「松林」と、あざやかに桜が咲き誇る「吉野山」を通して、名所や風景がいかに描き継がれてきたかをご覧いただきます。

長谷川等伯筆 安土桃山時代・16世紀 東京国立博物館蔵 (展示期間:4月13日(金)~5月6日(日))

長谷川等伯個人の代表作というばかりでなく、日本水墨画を代表する作品としてよく知られています。しかしその表現には、中国絵画からの強い影響も認められます。見る人を包み込むような広がり、どこかで見たような共感が沸き起こってきます。

10. 花鳥をつなぐ

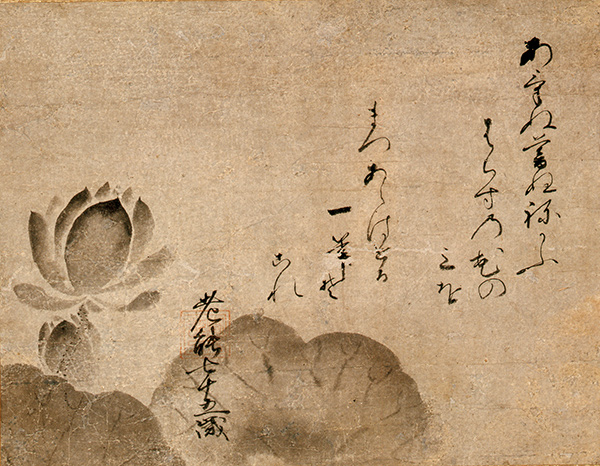

季節とともに移ろう身近な花や鳥。そこにはときに人々の心情が投影され、時を超えて愛されてきました。ここでは「蓮」と「雀」に注目し、中国から日本へとモチーフが伝承され、連綿と描き継がれた様相をご紹介します。

重要文化財 蓮図[はすず] 室町将軍の同朋衆として文化活動に関わった能阿弥(1397~1471)は、その没年にあたる文明3年(1471)「あけぬ暮ぬ ねがふはちすの花のみを まづあらはせる一筆ぞ これ」の歌とともにこの絵を遺しました。極楽浄土で往生者を包む蓮の花が中国・南宋時代の画僧、牧谿[もっけい]の画風で柔らかに表されています。 |

重要文化財 蓮池水禽図[れんちすいきんず] 向かって右には咲いた蓮と蕾が青々とした葉とともに夏の風に揺られ、左では花が散り始め、葉も変色し枯れてきています。蓮池水禽図は中国・江南の毘陵[びりょう]において盛んに描かれ、宋時代に蓮の蕾から開花、満開、衰枯へとうつろう時を表す定型ができました。 |

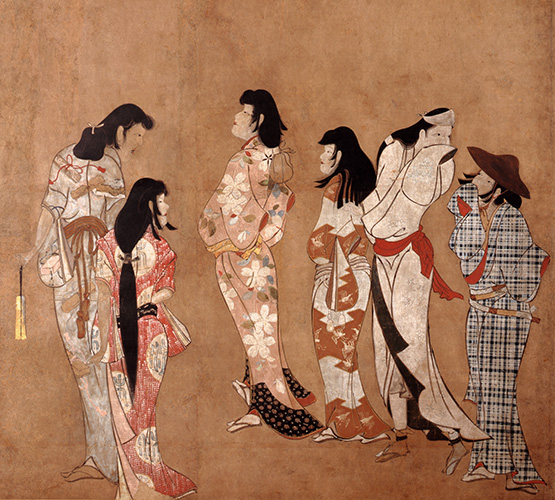

11. 人物をつなぐ

17世紀初頭、現世を楽しもうという時代風潮の高まりにあわせ、同時代の風俗や内面意識を主題とした人物画(風俗画)が描かれました。ここでは男女の間で交わされる視線と、古典文学からの図柄の転用が表す意味に注目して、風俗画や浮世絵の誕生について考えます。

江戸時代・17世紀 滋賀・彦根城博物館蔵 (展示期間:5月15日(火)~5月27日(日))

金地に15人の男女といくつかの器物を配しただけで、場の説明は極力控えられていますが、それぞれの配置によって物語が展開するような緊張感が生み出され、遊里の雰囲気が描き出されています。彦根藩主 井伊家に伝来した作品です。

重要文化財 湯女図[ゆなず] 絵の右側外に強い視線を送る女性たち。もとは、右側に画面が続き、そこに描かれた人物と呼応するような図柄の背の低い屛風だったと考えられます。女性の肉体を感じさせる描写と視線による広がりが、描かれた湯女の魅力となっています。 |

見返り美人図[みかえりびじんず] 切手になったことでよく知られる菱川師宣の代表作。当時流行のファッションに身を包み、体をくねるように振り返った姿が魅力的です。「菱川[ひしかわ]やうの吾妻俤[あずまおもかげ]」と謳われたのはこのような女性の姿だったのでしょう。 |

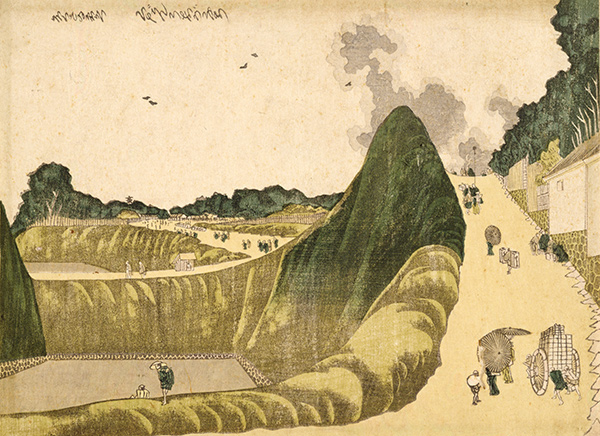

12. 古今をつなぐ

19世紀に西洋から新しい表現技法が一斉に流入すると、日本美術は大きく変容しました。ここでは大正から昭和にかけて活躍し、写実的画風で知られた洋画家・岸田劉生(1891~1929)を取り上げ、東洋絵画に学んで意識的にその伝統につながった様子を、その代表作「道路と土手と塀(切通之写生)[きりどおしのしゃせい]」と「野童女[やどうじょ]」からみていきます。

|

くだんうしがふち 葛飾北斎筆 江戸時代・19 世紀 東京国立博物館蔵 (展示期間:4月13日(金)~5月13日(日)) 北斎らの洋風風景画は、劉生のヒントになったのではないかと思わせます。九段坂は、白壁の土蔵と強い明暗が施された盛り上がる土坡[どは]とにはさまれ、上昇し、遠方が狭まり、頂点は短い水平線となって向こうに空が広がります。 |

開催概要 |

|||||||||||||

| 会 期 | 2018年4月13日(金) ~5月27日(日) | ||||||||||||

| 会 場 | 東京国立博物館 平成館(上野公園) | ||||||||||||

| 開館時間 | 9:30~17:00 ただし、金曜・土曜は21:00まで、日曜および4月30日(月・休)、5月3日(木・祝)は18:00まで開館 (入館は閉館の30分前まで) |

||||||||||||

| 休館日 | 月曜日(ただし4月30日(月・休)は開館) | ||||||||||||

| 観覧料金 | 一般1600円(1400円/1300円)、大学生1200円(1000円/900円)、高校生900円(700円/600円) 中学生以下無料

|

||||||||||||

| 交 通 | JR上野駅公園口・鶯谷駅南口より徒歩10分 東京メトロ銀座線・日比谷線上野駅、千代田線根津駅、京成電鉄京成上野駅より徒歩15分 |

||||||||||||

| 主 催 | 東京国立博物館、國華社、朝日新聞社、テレビ朝日、BS朝日 | ||||||||||||

| 協 賛 | 竹中工務店、凸版印刷、三菱商事 | ||||||||||||

| 協 力 |

あいおいニッセイ同和損保、日本通運 |

||||||||||||

| カタログ・音声ガイド | 展覧会カタログ(2500円)は、平成館会場内、およびミュージアムショップにて販売しています。音声ガイド(日本語、英語、中国語、韓国語)は550円でご利用いただけます。 | ||||||||||||

| お問合せ | 03-5777-8600 (ハローダイヤル) | ||||||||||||

| 展覧会公式サイト | http://meisaku2018.jp/ | ||||||||||||